Daniel A. Poling. Your Daddy Did Not Die. Greenberg, 1944.

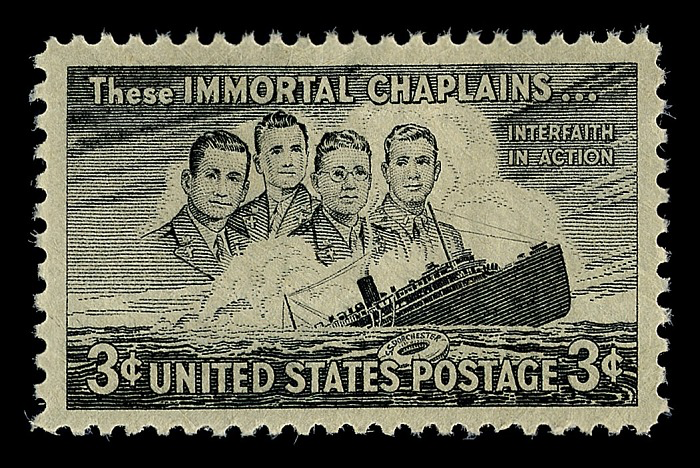

Readers who are familiar with tales of World War II may recall something of the four Immortal Chaplains. The American troop ship Dorchester was on its way to Europe in late 1942 with about 900 soldiers on board. It was early in the war when German U-boats were big trouble for the Allies. A German torpedo sank the ship. About 300 men survived. As the ship was sinking, the four chaplains assigned to the troops—one Jewish, one Catholic, two Protestant—gave their life jackets to other soldiers and went down with the ship, praying together.

One of the chaplains was Clark Poling. Your Daddy Did Not Die was written by Lt. Poling’s father as a kind of memoir about his son to Clark’s three-year-old son, Corky. It is homey and sentimental. I can recommend it as a good sketch about what life was like for the middle to upper middle class in the United States from 1910 until the beginning of World War II.

We learn a lot about the Poling family. It is honestly a little hard to keep track of everything. Clark’s mother died when he was a preschooler and his father remarried a widow with her own children. It seems, then, there were six children in the family, and maybe one born afterwards. If it seems a little hard to note this for sure, it is partly because the story is largely told in a nonlinear, rambling style.

The author himself was a fairly high-ranking (if such a term applies) clergyman. He was the assistant pastor for many years for Norman Vincent Peale, published Christian Herald magazine, and was a leader of Christian Endeavor, a ministry for church youth leaders. We get a sense of what mainline churches were like in the first half of the twentieth century. Religious belief and membership was pretty much taken for granted. I could not help thinking of Will Herberg’s acclaimed 1955 sociological study Protestant, Catholic, Jew. Back then, every American was one of those three religions. Atheists and skeptics were Communists or (before the war) Fascists.

No reader can seriously question the author’s faith or the faith of his son, but we note a generational shift. Clark and his brother Daniel, Jr., who was also a pastor, were the seventh generation of clergymen in the family going back to the Puritans. Clark’s grandfather was a Baptist missionary to Oregon who worked in rural areas and among Indians. The author calls him a Fundamentalist, that is someone who subscribed to the teaching of The Fundamentals, including the atoning work of Jesus alone for salvation and the complete inspiration and infallibility of the Bible.

From his tone, we sense the author was less strict. His son had doubts about parts of the Bible such as the virgin birth of Jesus, but still believed in God and in the Christian religion. We can see in this the gradual shift of emphasis in many mainline churches that continues until the present.

There is no real theme to the book, but there are fond memories of the fallen chaplain. We learn, for example, that in the war a greater percentage of chaplains were killed than any other army corps except for the Air Corps. They were often in harm’s way but were noncombatants. Readers can appreciate the family’s sacrifice. While Lt. Poling did have about two years with Corky before he left for Europe, he never did meet his daughter whom his wife was carrying when the Dorchester went down. As they say, freedom is never free.

Lt. Poling had only been in the army about a year when he was killed. That was true of two of the other chaplains as well. However, because of his job, he got to know hundreds of soldiers during that time. Some people, especially mothers, often worry that the rough life of many soldiers would corrupt their sons. He observed that young men who were raised well and had positive character traits still had them in the service. Their experiences would affect them, yes, but their basic personalities, whether for good or evil, would come forth in the military as much as any other occupation.

From what I have seen, that is still true today. To mothers I would say, if you want your sons to become men, the service is a good option. Yes, there are great risks, but at the same time it truly tests their character. I still recommend the military experience for any young man who can pass the physical.

Above photo is of the 1948 Immortal Chaplains Commemorative Postage Stamp. I believe Lt. Poling is second from left. Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons.