Richard Webb, Jr. Boats Against the Current: The Honeymoon Summer of Scott and Zelda, Westport, Connecticut 1920. New York: Prospecta P, 2018. Print.

This nicely researched picture history of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald is meant to go along with the documentary of the same name produced by the author. It works well. It has numerous photographs and makes a case that many things that inspired Fitzgerald in his writing, especially The Great Gatsby, came from the year he and his new bride spent along the shore of Long Island Sound in Connecticut.

Everyone recognizes that the Marietta, Connecticut, where much of The Beautiful and Damned takes place is based on their stay there, but Webb takes up the hypothesis that a lot of what would appear in The Great Gatsby also comes from things Fitzgerald observed and heard about during their year in Connecticut.

This is not so much a review of the book as a collection of notes taken from the book. It should give us all a better understanding and appreciation of Gatsby at any rate.

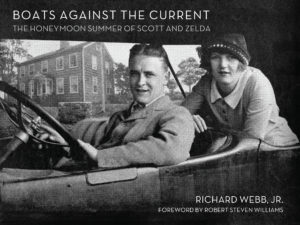

The cover photo is an iconic photo of the Fitzgeralds taken in a car in front of the house they rented at 244 Compo Road in Westport. The photo can also be seen on the Scott and Zelda web site. There is a photo on page 110 of Zelda which shows how attractive Zelda could look. It sounds like she was able to drive men crazy, and not just Scott.

Fitzgerald’s college friend Alexander McKaig wrote in his diary that Zelda was “a very dramatic, provincial Southern belle. The sad thing is that Fitz is completely overwhelmed by Zelda’s personality…she’s the role model for all the female characters in his novels…” (89)

He also wrote, “She’s without a doubt, the most beautiful and intelligent woman I have met.” (90) About a visit he made to them, he wrote: “Went to visit Fizgeralds in Westport…stayed drunk for two weeks straight. Atmosphere of crime, lust, sensuality, pervaded the home.” (90)

Webb notes that “more than one of Scott’s friends declared that they were in love with her.” (81) This reminds me of when Daisy arrives at her cousin Nick’s house and Nick is alone (she is not aware that this is done so Gatsby can reunite with her). She asks Nick, “Are you in love with me?” Webb tells us Fitzgerald often noted things Zelda said. This sounds like something she might have said, perhaps on more than one occasion, to different men.

Webb noted that the critic and author Van Wyck Brooks lived nearby at the time and met the Fitzgeralds. His book The Ordeal of Mark Twain was given to Scott while he was working on Gatsby and may have inspired him. Webb says:

In locating the source of American worship of success and riches, Fitzgerald probably, not by coincidence, reproduced Brooks’ thesis: Fitzgerald’s criticism of American worship of success in The Great Gatsby carried the thrust of Brooks’ own thought. (93)

Professor John Henry Raleigh would write:

America had produced an idealism so impalpable that it had lost touch with reality (Gatsby) and materialism so heavy that it was inhuman (Tom Buchanan). (93)

The short story “Dice, Brassknuckles, and Guitar” prefigures Gatsby in a few ways. There is a family in the story named Katzby, and the main character tells someone, “You’re better than all of them put together, Jim.”

While the Fitzgeralds’ landlord was no Gatsby, their house bordered the property of F. E. Lewis, a large estate. Lewis gave them permission to cut across his property to get to a nearby beach. Lewis occasionally had enormous parties. The parties were not as wild as Gatsby’s; indeed, children were usually invited. But they could be extravagant.

One party held in 1917 to raise money for different war charities including the Red Cross had entertainment for all ages. It included camels, elephants, and clowns for the kids. There were vaudeville acts, dance troupes, and a cowboy and Indian show. Belasco, who is mentioned in Gatsby, attended. Entertainment included dancer Anna Pavlova, magician Henry Houdini, and actresses Marie Dressler and Ina Claire. Even John Philip Sousa wrote a composition for one of Lewis’s parties.

Another nearby mansion, now part of the Green Farms Academy, was owned by E. T. Bedford. He was very philanthropic, especially to local causes. He had many political and social contacts. He is even mentioned as an example to emulate in Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. We are reminded of Gatsby’s connection with the police commissioner and of some of the political figures who attended his parties.

Neither Lewis nor Bedford had any criminal connections, but we can see traces of Jay Gatsby in these men.

Webb notes that when he was researching his film, he contacted a Lewis descendant who at first refused to talk to him. “My grandfather was not a criminal, Gatsby was,” he complained. Webb eventually was able to interview him, so we do get a sense of the lifestyle of this very wealthy man in 1920.

Webb does mention some bootleggers that Fitzgerald may have known or at least had heard of. While he does recognize that the character of Wolfsheim is based on Arnold Rothstein, there may also have been some Westport connections as well. A Jewish gangster Jacob Rosenzweig (a.k.a. Bald Jack Rose) supplied much of the booze to Westport establishments during Prohibition.

A low-level bootlegger Max Von Gerlach who would become a car dealer closed a letter to Fitzgerald by calling him “old sport.” Later Zelda would say that he was one of the models for Gatsby.

Webb notes that the author Owen Johnson had quite an influence on both Scott and Zelda. His novel The Salamander (1913) was made into a film in 1916 that the teenaged Zelda saw several times and announced that it described the way she wanted to be. Johnson later apparently felt that he had invented the flapper before Fitzgerald, but Scott got the credit. Zelda called Scott “Dodo,” a nickname for one of the characters in The Salamander. Their favorite speakeasy was the Jungle Club, a hangout mentioned in the pre-Prohibition Johnson novel.

Scott himself said that Johnson’s Stover at Yale (1912) was “‘a textbook’ for his generation.” (150) The character Stover also appears in Johnson’s prep school story The Varmint (1910), another book Scott liked. He noted in a 1921 review how he appreciated Johnson’s latest, The Wasted Generation. The title has echoes of Stein’s Lost Generation.

Page 154 of Boats Against the Current lists a number of characters based on acquaintances of Fitzgerald, especially in The Beautiful and Damned since a good part of that is set in Westport.

The Fitzgeralds took an automobile trip from Connecticut to Alabama which Scott would serialize as The Cruise of the Rolling Junk. A modern edition of the story includes this observation in the introduction by Julian Evans:

The Fitzgeralds’ destination is not just ante-bellum but, as he makes clear, prelapsarian America, and their journey is not just into the South, but into the past, an impossible return, as Gatsby’s is. (158)

Prelapsarian is an appropriate word here. Especially so, if we consider Tanner’s thesis about the New Testament burlesque in Gatsby.

Webb’s main thesis is really that Scott and Zelda were truly happy their first year of marriage. Yes, they drank a lot, but Scott had a good income from his first novel, and they were still very much in love. It seems that even by the time Scott began writing Gatsby, there were some difficulties in their relationship, and Gatsby’s romantic recollection of Daisy from five years earlier may well have paralleled what Scott was going through himself at the time.

When Gatsby tells Nick “Of course you can” repeat the past, that may be what Scott himself was hoping for. While Webb notes different people like Lewis, Bedford, Von Gerlach, and others may have contributed to the outward figure of Gatsby, the real character of Gatsby is based on Fitzgerald himself, as Fitzgerald himself admitted.

Professor Walter Raubicheck calls the last page of The Great Gatsby “the most celebrated page in American literature.” (63) The only other pages that I have read that might surpass it are the first and last from Moby Dick. Why quibble?

Webb was able to interview Sam Waterston, who played Nick Carraway in the 1974 film version of Gatsby. The actor read that last page of Gatsby in such a way that it brought tears to everyone’s eyes.

Webb interviewed some descendants of the key figures in his book including Charles Scribner III, a grandson of F. E. Lewis, and Eleanor “Bobbie” Lanahan, the only child of Scott and Zelda’s only child, Scottie.

Scottie would write:

My father was on the scene when we started to lose our way during Gatsby’s time—and he recorded it all—the generosity, the greed, the cynicism, the magnificence and the waste that was America between the two world wars—people read him now for clues and guidelines as if by understanding him in his Beautiful and Damned period they could see more clearly what’s wrong. (63)

It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.

7 thoughts on “Boats Against the Current – Review”