Philip K. Dick. The Man in the High Castle. New York: Putnam, 1962. Print.

Let me tell you why I read The Man in the High Castle. I teach Henry IV Part 1 in my Shakespeare class. The play portrays an unsuccessful rebellion against King Henry IV of England led by three men: the Earl of Northumberland, who holds sway in the North of England; Owen Glendower, guerilla leader of a movement to make Wales independent; and Edmund Mortimer, who claims that he (or his nephew) is the legitimate heir to the throne.

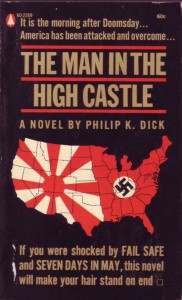

There is a scene where these three parties take a map of Britain and discuss how they will divide England into three smaller countries if they succeed. I try to have my class imagine how shocking this would be to Shakespeare’s English audiences—cutting up the motherland in thirds! I tell them how I remember when I was a kid in the sixties there was a book that imagined what things would have been like if the Axis powers had won World War II. A friend of mine had it. The cover was a picture of the 48 contiguous United States with a rising sun on the Western half of the map and a swastika on the Eastern half. Wow! I remember thinking, that might have happened! It was a scary thought.

As I was preparing the class this year, I happened to wonder what the book was. I only saw the cover of this paperback once or twice fifty years ago and had no idea of the book’s title. I did a web search on books of World War II alternate history. Nearly all the alternate history books have been written within the last twenty years. For a few years it was a kind of fad like the horror mash-ups are now.

I remember reading one fascinating essay based on Confederate records on what might have happened if the Confederacy had succeeded in seceding. I picked up a novel based on a similar premise, but I honestly found it too confusing and never finished it. The novel was clever, I suppose, but I felt as if I was reading something by the Shaaras if they had converted to Gnosticism. It was too weird.

I found one book in my search from the sixties, and the author was, of all people, Philip K. Dick. None of the book covers on Amazon had the map that I remembered, but his The Man in the High Castle surely sounded like a possibility. Virtually everything I had read by Dick was straight science fiction with robots, space travel, or weird mind control. He is best known today for films based on his stories such as Blade Runner, Total Recall, and Minority Report. I have since learned that the BBC came out with a TV version of The Man in the High Castle this year.

It happens that a new teacher at our school is a comic collector. Recently he mentioned that he collected Sci-Fi books as well. I asked him about The Man in the High Castle with the cover I described. He knew exactly what I was talking about and scanned the cover for me so I could show it to my class. After going through all that, I had to read the book.

The hardcover I got from the local library had a different jacket design, but the story has aged pretty well. Although the book was in the library’s Science Fiction section, The Man in the High Castle is not Sci-Fi. Dick himself may have been frustrated with this pigeonholing of his work. Three people in the novel are discussing a popular book which itself a work of alternate history. One reader named Paul calls it an “interesting form of fiction possibly within the genre of science fiction.” He immediately is challenged:

“Oh no,” Betty disagreed. “No science in it. Nor set in future. Science fiction deals with future, in particular future where science has advanced over now. Book fits neither premise” (91)

They are discussing a book which has become popular in the Japanese-controlled part of North America. It is banned in the German-controlled Eastern States of America. This imaginary novel, The Grasshopper Lies Heavy, speculates what would have happened if the Allies had won the war instead of the Axis—a kind of alternate history within an alternate history.

Most of The Man in the High Castle is set in San Francisco, now a part of the Japanese Empire’s Pacific States of America (PSA). Some of the story takes place in Colorado and Wyoming which belong to Japan’s Rocky Mountain States of America. The Axis powers won because of German rocket technology and their development of the hydrogen bomb.

The Japanese rule their realms somewhat benevolently, at least for white Americans. While all the top government and business positions are held by Japanese, white Americans are respected for their creativity and history. Chinese are servants and laborers, like the coolies during World War II. Surviving Negroes are often slaves.

Germany has been more ruthless in its conquests. Jews are exterminated. One character in San Francisco is a New York Jew who settled there after the war ended in 1947 before they could round him up. The Germans have bombed most of the continent of Africa to eliminate blacks there. They are in the process of the exterminating the remaining blacks in their North and South American territories. They were in the process of exterminating all the European Slavs but decided to allow those that remained to resettle in their Central Asian “homeland.”

Germany has the rocket expertise and has landed on the moon and is making plans to go to Mars. One popular joke told by comedian Bob Hope is that the Germans will land on Mars and find that the planet is inhabited by Jews! The book notes that most American comedians were Jewish and have been killed. Commercial passenger rockets can fly between Germany and California in less than an hour.

But this is all incidental. The story involves a number of characters whose lives overlap in casual ways but together tell a pointed story.

It is now 1962. The current German führer Martin Bormann has died, and there is an internal struggle to see who will rule the German half of the world. Will it be Goebbels? Göring? Heydrich? or perhaps a dark horse? It also appears that just as Hitler double-crossed the Soviets in 1941, the 1962 Germans were thinking of double-crossing the Japanese.

A Swedish businessman who has gotten wind of the plot has rocketed to San Francisco to try to warn the appropriate Japanese army authority who himself is taking a boat across the Pacific to get there. Meanwhile German agents are trying to assassinate the Swede before he can make contact. When a Japanese official speaks to the businessman in Swedish and gets no response, the Japanese begin to wonder who he really is.

Most of the people in the story are not political figures. Since Western North America is now ruled by Asians, the country now reflects a more Asian culture than before. Many Americans consult the I Ching for guidance. There is the antiques dealer whose clients include wealthy Japanese. The New York Jew mentioned earlier is now an antiques salesman who discovers that one of his trusted sources is a forger. His divorced wife in Colorado is making arrangements to visit the author of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy who lives in Wyoming. The mid-level Japanese bureaucrat who is arranging the meeting between the Swede and the Japanese general has no idea that the meeting is about the German double-cross.

The actual man in the high castle is neither a Bavarian Nazi nor a Japanese secret policeman, but Abendsen (“evening son” or “eve’s son”), the author of The Grasshopper Lies Heavy. Although he lives in relative safety in Japanese-controlled Wyoming, an Italian assassin is trying to silence him as well.

Abendsen makes some clever observations about the nature of victory in war as Dick suggests there is more to life than meets the eye. Is life fated as both the I Ching and the “scientific” German and Japanese determinists believe? The discovery of the true theme that the man in the high castle reveals is ironic, clever, and makes a satisfying ending to the story. Though alternate history, The Man in the High Castle is not gnostic.

3 thoughts on “The Man in the High Castle – Review”